Syrian Crisis: Back to Square One?

After the recent fall of Aleppo to the Syrian regime and the inauguration of President Donald Trump in the United States, Syria found itself in a fundamentally new situation. Russia engaged in an enormous show of force in Aleppo, one met with silence by an outgoing Obama administration hesitant about spending its final days embroiled in the Syrian conflict. Moscow sought a victory in the city before Trump took office, so as to strengthen its bargaining hand with the incoming American administration.

Russian President Vladimir Putin expects that the time is ripe for friendlier negotiations with Trump. Furthermore, Moscow can take satisfaction in the fact that it is viewed by the administration as a credible partner in the fight against what Trump regards as an overriding threat, namely “radical Islamic terrorism.” The incoming administration may pursue greater cooperation, and even look to replicate Russian successes elsewhere, possibly in Raqqa and Idlib.

Dealing with the two Syrias

What is becoming more probable is that a new map of Syria is in the making, whereby the chaotic fragmentation of the country will move gradually toward an ordered form of cantonization. The existing de facto statelets may gradually take on a more recognized quality amid widespread decentralization of authority across the country.

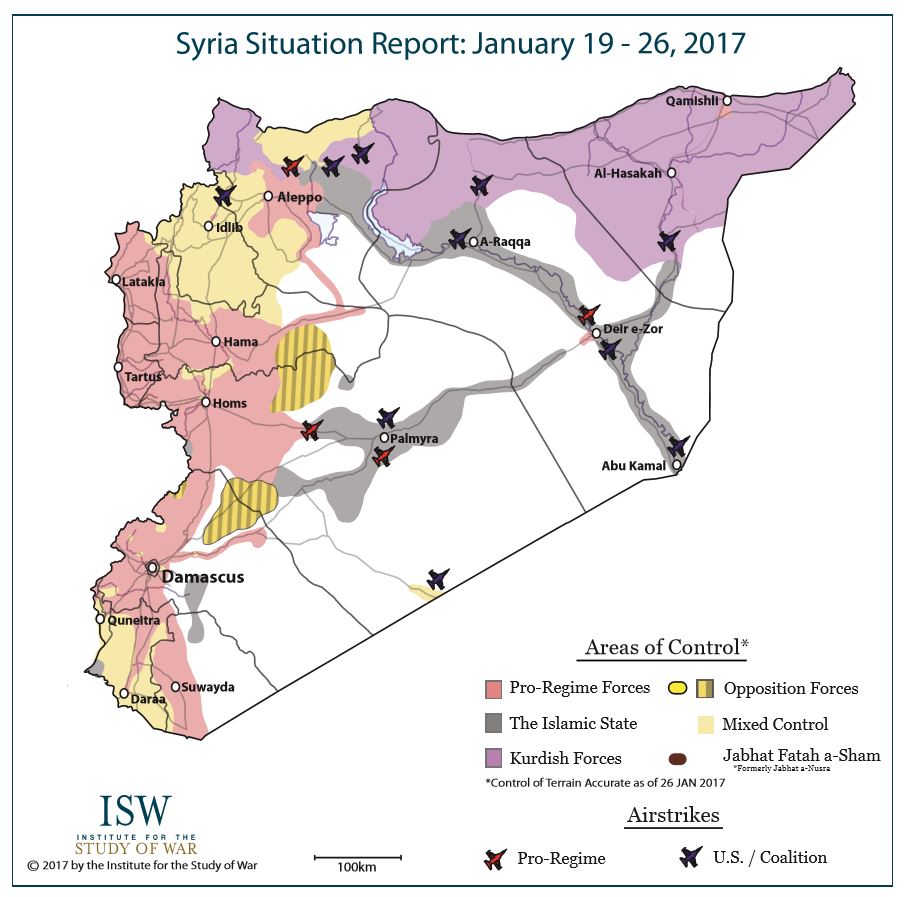

For now, Syria’s territory is divided into two broad areas, with contrary dynamics in each. The fall of Aleppo, alongside the ongoing “cleansing” by the regime of the suburbs of Damascus, has effectively consolidated a regime-controlled sanctuary—albeit an imperfect one—that has been termed “useful Syria.” This has left the rest of the country under the sway of numerous factions, most of them radical Islamists, coexisting with, or more often fighting against, the remnants of moderate armed rebel factions.

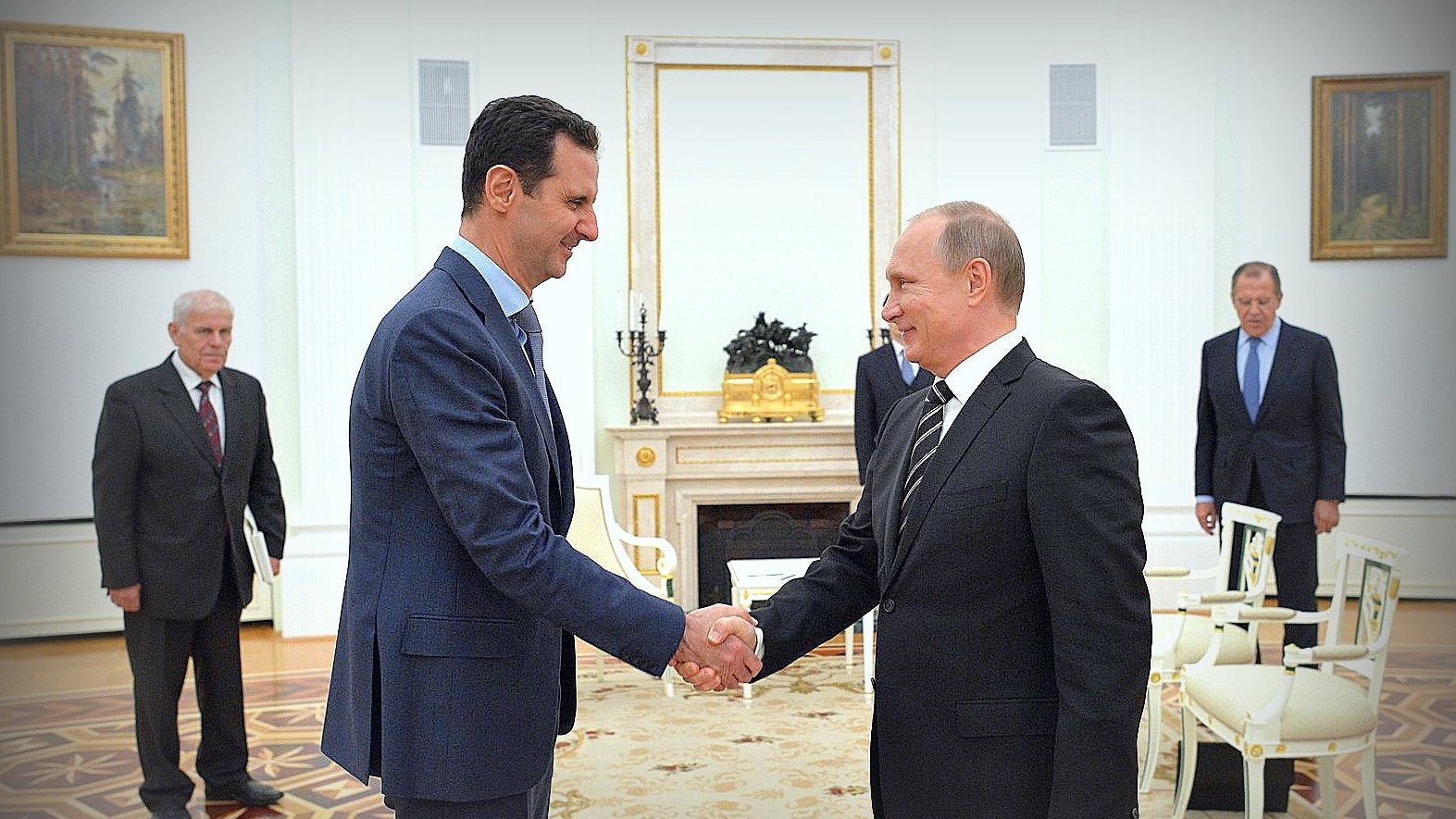

In the Syrian regime’s mind, “useful Syria” is the platform from which it can launch operations to regain more land. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad seeks to ensure that his survival is a part of any Putin-Trump agreement. He seeks the rehabilitation of his regime, and wants to be recognized internationally as an unavoidable player in the Syrian endgame. This is something Assad can realistically expect given the new climate in the West and a mindset there and elsewhere that tends to accept him as a lesser evil.

Russia takes a somewhat different view of the Syrian landscape. To Putin, regime areas can serve as a strong card in negotiations with the United States over a political package for Syria and Russia’s future in it. Now that the small parts of eastern Syria that were still under regime control and Russian protection, namely Palmyra and Deir Ezzor, have either fallen again to the Islamic State, or risk doing so, Putin hopes to use talks with Trump to gain approval for Russia to recapture Syria’s majority Sunni areas, defeat the remaining opposition groups, and then introduce some form of decentralization, which the Russians realize is the only way for Syria to remain one, and for Russian interests to be preserved.

A second part of this bargain would center on “useful Syria” itself—its shape and governance, its protectors, and the role that Bashar al-Assad would play in it. There, Russia needs U.S. acquiescence to better deal with a constrained regime and its equally constrained Iranian and Shia backers, as well as Turkey and the Gulf states. In other words, as Russia maneuvers between the myriad political actors involved in Syria, an understanding with the Americans would provide it with much greater leeway to pursue its political preferences.

Astana, a door to Russian objectives?

It’s in this context that the Astana conference was organized this week, under the sponsorship of Russia, Turkey, and Iran. The immediate aim of the gathering was to consolidate a more durable ceasefire in Syria. However Moscow, which dominated preparations for the conference, has also sought to transform the victory in Aleppo into sustainable political gains. Putin’s ultimate intention is to shape a future grand scheme for Syria by achieving three primary goals.

The first is to monopolize negotiations over Syria, in which previously the United States had played a major role as well. Putin would like to exploit the lack of focus in Washington due to a chaotic transition and take the lead in any future talks. Today, Russia is in the driver’s seat, while Turkey and Iran are in the passenger seats. As for the U.S. it may well be in the trunk.

Second, in Russia’s calculations the Astana process should lead not only to a scaling down of the Syrian opposition’s ambitions and expectations, but also to a remodeling of the opposition itself. Because of their contentious nature, the negotiations may further divide the opposition, whereby the groups least amenable to compromise would lose currency. This would allow the Russians to effectively choose the regime’s interlocutors.

Third, any kind of framework that comes out of Astana may gradually replace the Geneva framework that had previously been in place, and that sought a transitional arrangement for Assad’s replacement. Geneva had numerous stakeholders, but Astana may better reflect what the Russians regard as a more realistic outcome in Syria: the replacement of any notions of a unified, democratic Syria with the consolidation of existing statelets and zones of influence through local truces and reconciliations. These would later be legalized through a permanent decentralization scheme. In this future Syrian state a weakened Assad may remain in the picture for a long time, though very likely supported by new institutions, including a military council that would include regime generals and former rebels. This would be accompanied by a largely cosmetic national-unity government that could introduce minimal reforms on matters not vital for regime survival and oversee vital reconstruction plans for the country.

This is the process into which the Trump administration would probably be invited. The new U.S. president may not have objections to such a formula for Syria. Revealingly, in the final weeks of the presidential campaign one of his sons met in Paris with Syrian opposition figures considered acceptable by the regime. The meeting was co-hosted by Randa Qassis, a protégée of Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, and one of those whom many believe will play a prominent role in any new Syrian government. More recently, U.S. Representative Tulsi Gabbard, a Democrat who had recently met with Donald Trump, visited Damascus on a “fact-finding trip,” during which she may have met with Bashar al-Assad himself.

If Russia’s efforts are to succeed after Astana, and if the ideas favored by Moscow are picked up, legitimized, and amplified by a series of new international conferences on Syria, such as the planned Geneva conference in February, Putin will have succeeded in doing several things: putting a lid on the Syrian people’s revolution; temporarily shelving the question of Assad’s future; and gradually transforming the de facto political and military situation Russia has created into one that gains international legal sanction.

All this suggests that 2017 may be a year in which the Syrians realize that their conflict opens up on two alternatives: It may be frozen as the focus shifts solely to combating terrorism; or, because the future of the Assad regime is left unaddressed, Syria will return to square one. After years of terrible suffering, these options are hardly ideal.